If you’ve been following this series, you know that we’ve been focusing on the disruptive potential of Artificial intelligence. Going off the “Black Swan” theory, we’ve noticed that relatively few people in leadership positions are seriously talking about the implications of AI, which suggests that this is a bit of a blind spot for leaders.

But it’s not the only disruptive force on the horizon, and while I am fairly confident in my analysis of this situation - the methodology of which is a topic for another post - our overall point has been that disruption is inevitable; the mechanism of disruption matters less than the actual disruption itself. Change is the common factor with disruption, and change can be extremely difficult for people. During difficult times, it is often the quality of leadership that makes the difference between good and bad outcomes. But why is it that disruption is inevitable? That’s what this Sunday story is all about.

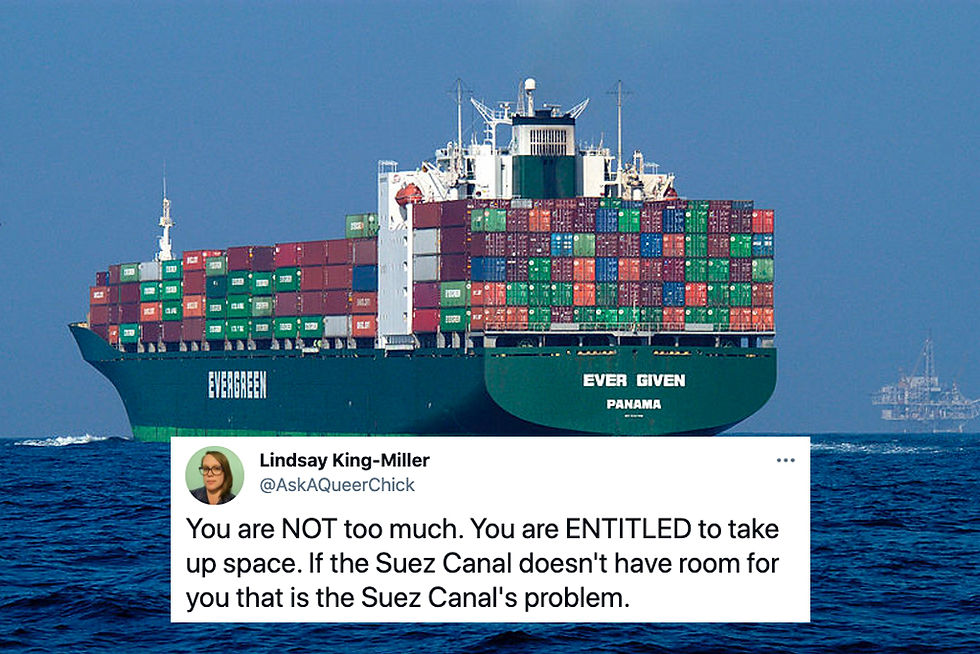

It turns out, the way our society has structured itself means that a major disruption to our way of being and doing is essentially inevitable - and if you don’t inherently know that to be true we encourage you to take a look at the world since 2020 and ask yourself this: Do you honestly think things will magically settle down after pandemics, wars around the world, and boats getting stuck sideways in canals causing the price of avocado toast to skyrocket half a world away?

Our answer is “Nah, it’s likely not calming down anytime soon”, and that last example above which is referring to the Evergiven incident in the Suez Canal is not just a flippant pop culture reference - it’s a great example of exactly why our world is prone to disruption today in a way that may not have been before.

Charles Perrow’s “Normal Accidents” (1984) describes modern society as one that is ripe for disruption due to the nature of our how society is organized. Put simply, our systems are no longer simple, they are highly complex, and they are interdependent on one another in such a way that a failure in one system is highly likely to cascade into a failure in multiple other systems and in sometimes unpredictable ways. Let’s look at a simple example:

200 years ago, most of the food you purchased would have been grown within a few hundred kilometres of where you lived. Refrigeration and railroads weren’t a thing yet, so food preservation methods were primarily used by individuals to keep their cellars full, as opposed to being about shipping goods to far away markets. There was a seasonality to a person’s food - fresh greens in summer and fall, stored and preserved foods to get through the winter, and repeat it the following year. Disasters absolutely happened - a bad harvest could spell disaster for entire communities - but they were largely a result of major disruptions like a drought or other weather event, and these events could be logically connected to the problem at hand, and they were somewhat of a known quantity, so folks tended to have a lot of extra jars in the root cellar for just such an event. Localized disasters happened too, but because the system of obtaining food was “loosely coupled” as Perrow calls it, a localized disaster in one part of the system doesn’t necessarily cascade to every other part of the system. In other words, a disaster could befall a community and totally destroy its food supply, and that community could be entirely wiped out, but that is unlikely to have an impact on every other community in the world.

Now contrast that with the modern food system. Most people in the Western world get their food at a supermarket, and the variety is mind-blowing. The very idea of seasonality no longer applies, replaced instead by an expectation that we can eat what we want, when we want, and we are totally at ease with seeing avocados in February in Canada. That’s great, except the systems and machines that create that situation are highly complex and very tightly coupled. Grocery stores work on a “Just in time” delivery model, which means that trucks are constantly travelling between your nation’s port cities and the various grocery stores to ensure those shelves are full. If a giant ship decides to park itself sideways in the Suez Canal and blocks trade traffic for a couple of weeks or if a global pandemic prevents those trucks from crossing borders - something that would have been mostly irrelevant to our local food security 150 years ago - the end result is empty grocery store shelves. Remember how hard it was to find toilet paper?

This is because our current society relies heavily on highly complex systems (like the food distribution system) that are what Perrow called tightly coupled. That’s just a fancy way of saying that failure in one system will result in a failure in many other seemingly unrelated but connected systems. Perrow focused on highly complex tightly coupled systems in high-risk technology like Nuclear power plants, where a cascade failure due to a problem in one small system can cause substantial loss in life, but now 40 years after his writings, we have an entirely new landscape of technology to consider.

A question that illustrates this landscape is this: What happens if the internet fails? Banking, shopping, the entirety of the stock market, scheduling of those trucks full of groceries and boats that deliver them, airplanes, workers; distribution of medical assistance and critical communications are all tightly coupled with the internet, and a failure in our internet infrastructure means a significant disruption in our ability to live our lives. We already know what that is like in Canada because in 2022, a failure of Roger’s systems in Toronto resulted in Canadians across the country being totally unable to access their financial resources.

Now, we are not saying that the apocalypse is nigh and everyone should stock up on beans and bullets and lock themselves in a bunker. The main consistent thing with all of the disruptions we’ve listed above - the banking crisis caused by Rogers, the Evergiven Suez incident, or the Pandemic-related bog-roll crisis of 2020 all have one thing in common: We got through it. We survived having to ration our TP. Rogers got banking online again a day or two later. And the Evergiven incident gave us weeks worth of amazing memes to chuckle at as we saw (and are still seeing) how the prices we pay every day are related to the global supply chains around the world, but we survived, and we’ve kept on going.

But it was uncomfortable, wasn’t it? Remember struggling with the ethics of “stocking up” and contrasting that with wanting to make sure your family had what you needed in the uncertainty of COVID? Are you eating as well as you were a few years ago, or have you had to make some conscious decisions to forgo some old favourites because of the cost of living?

That is what disruption is about - it’s uncomfortable for people. And, like Colonel Hackworth (whose story we tell in our white paper) your leadership can make the difference in that discomfort.

It is important to note that we don’t know how much discomfort our system can withstand. The incidents I’ve identified have tested our flexibility to sociotechnical disasters, and like a wooden stick, it appears our systems can bend before they break. But also like the stick - we never really know which degree of bend is going to be the degree-too-far that results in splinters and snapping. In other words, we don’t know how flexible our system is, and what it can bounce back from versus what it cannot. This, too, is a characteristic of sociotechnical systems - it’s rarely one challenge that ruins the day. It’s the unlucky alignment of several issues that results in a major disaster. Let’s look at one final example for this blog post: TWA Flight 800.

If you remember the news from the late 1990s, TWA Flight 800 was all over it. This was the 747 that took off from the Eastern USA and soon after exploded mid-flight; there were all kinds of conspiracies about a missile hitting it, and for good reason - at the time of TWA 800, the platform (the Boeing 747) had been flying for decades, and they never had just exploded in mid-flight the way TWA-800 did. For many, a missile was the only explanation - clearly, if there was something wrong with the plane, someone would have found it by now, right?Well, wrong - turns out there was something wrong with the plane. The short version is that three factors had to be present for TWA Flight 800 to explode. The actual explosion was caused by a fuel pump that was creating sparks. And wouldn’t you know it, that exact same fuel pump was installed on every other 747 for decades at this point? So why didn’t they blow up?

Two other factors: First, TWA Flight 800 didn’t have full tanks. The half-empty tanks meant that fuel vapour was able to combine with air in the tanks to create the perfect fuel-air mixture for combustion. But again - other 747s had flown with half-empty tanks too and never exploded, so what gives with TWA Flight 800?

It was the temperature on the ground right before they left. The ground temperature heated the tanks in such a way that it excited the fuel just enough for the fuel/air vapour to be just right for a big boom. The fuel pump sparked and ignited the tanks and destroyed the plane in mid-flight. Every other 747 had this exact same situation possible - but they never flew with all three elements at the same time.

That’s modern disasters. It’s not the stuck boat or the failed bank or the political protest that gets you - it’s the stuck boat on the same day as the failed bank which is on the same day as a protest in a nations capital has the fires stoked by an oligarch into raiding the capitol building.

Disruption is inevitable - we believe AI is going to be a big disruptor, but we also believe there are a few more worth keeping an eye on. The big takeaway here is: it does not matter what causes the disruption. What matters is that when folks are disrupted, it has an impact, and leaders can help determine if that impact is going to be positive or negative for the people they serve. And this week, we're giving away $5,000 worth of custom tabletop exercise to one lucky LinkedIn follower which is specifically designed to help you prepare to lead through the coming disruption. Stay tuned for more!

See you next Sunday where we’ll go over a few of the other likely vectors of disruption to prepare for, and keep an eye on our page for info on how to win the free Tabletop Training Exercises!

Comments